Civic Planning for Levitical Towns (Numbers 35:1-5)

Bible Commentary / Produced by TOW Project

Unlike the rest of the tribes, the Levites were to live in towns scattered throughout the Promised Land where they could teach the people the law and apply it in local courts. Numbers 35:2-5 details the amount of pasture land each town should have. Measuring from the edge of town, the area for pasture was to extend outward a thousand cubits (about 1,500 feet) in each direction, east, south, west, and north.

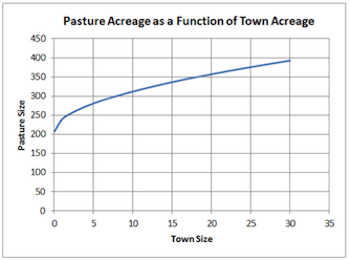

Jacob Milgrom has shown that this geographical layout was a realistic exercise in town planning.[1] The diagram shows a town with pastureland extending beyond the town diameter in each direction. As the town diameter grows and absorbs the closest pasture, additional pasture land is added so that the pasture remains 1,000 cubits beyond the town limits in each direction. (In the diagram the shaded areas remain the same size as they move outward, but the cross-hatched areas get wider as the town center gets wider.)

You shall measure, outside the town, for the east side two thousand cubits, for the south side two thousand cubits, for the west side two thousand cubits, and for the north side two thousand cubits, with the town in the middle (Num. 35:5).

Mathematically, as the town grows, so does the area of its pasture land, but at a lower rate than the area of the inhabited town center. That means the population is growing faster than agricultural area. For this to continue, agricultural productivity per square meter must increase. Each herder must supply food to more people, freeing more of the population for industrial and service jobs. This is exactly what is required for economic and cultural development. To be sure, the town planning doesn’t cause productivity to increase, but it creates a social-economic structure adapted for rising productivity. It is a remarkably sophisticated example of civic policy creating conditions for sustainable economic growth.

Mathematically, as the town grows, so does the area of its pasture land, but at a lower rate than the area of the inhabited town center. That means the population is growing faster than agricultural area. For this to continue, agricultural productivity per square meter must increase. Each herder must supply food to more people, freeing more of the population for industrial and service jobs. This is exactly what is required for economic and cultural development. To be sure, the town planning doesn’t cause productivity to increase, but it creates a social-economic structure adapted for rising productivity. It is a remarkably sophisticated example of civic policy creating conditions for sustainable economic growth.

This passage in Numbers 35:5 illustrates again the detailed attention God pays to enabling human work that sustains people and creates economic well-being. If God troubles to instruct Moses on civic planning, based on semi-geometrical growth of pastureland, doesn’t it suggest that God’s people today should vigorously pursue all the professions, crafts, arts, academics, and other disciplines that sustain and prosper communities and nations? Perhaps churches and Christians could do more to encourage and celebrate its members’ excellence in all fields of endeavor. Perhaps Christian workers could do more to become excellent at our work as a way of serving our Lord. Is there any reason to believe that excellent city planning, economics, childcare, or customer service bring less glory to God than heartfelt worship, prayer, or Bible study?